If there is one designer who has been associated with Mary Jane Denzer in White Plains more than any other over the last 42 years, it is Neil Bieff. Indeed, so often has MJD featured his delicately textured creations, which both caress a woman’s silhouette and flow around her, that store co-owner Debra O’Shea has affectionately described him as a kind of “in-house designer”.

“There’s something about the timelessness and comfort of his clothes,” added O’Shea, who co-owns the store with Anastasia Cucinella. “We have women who wore his dresses to their children’s bar mitzvahs and bat mitzvahs, who now are coming in and looking at gowns for their children’s weddings.”

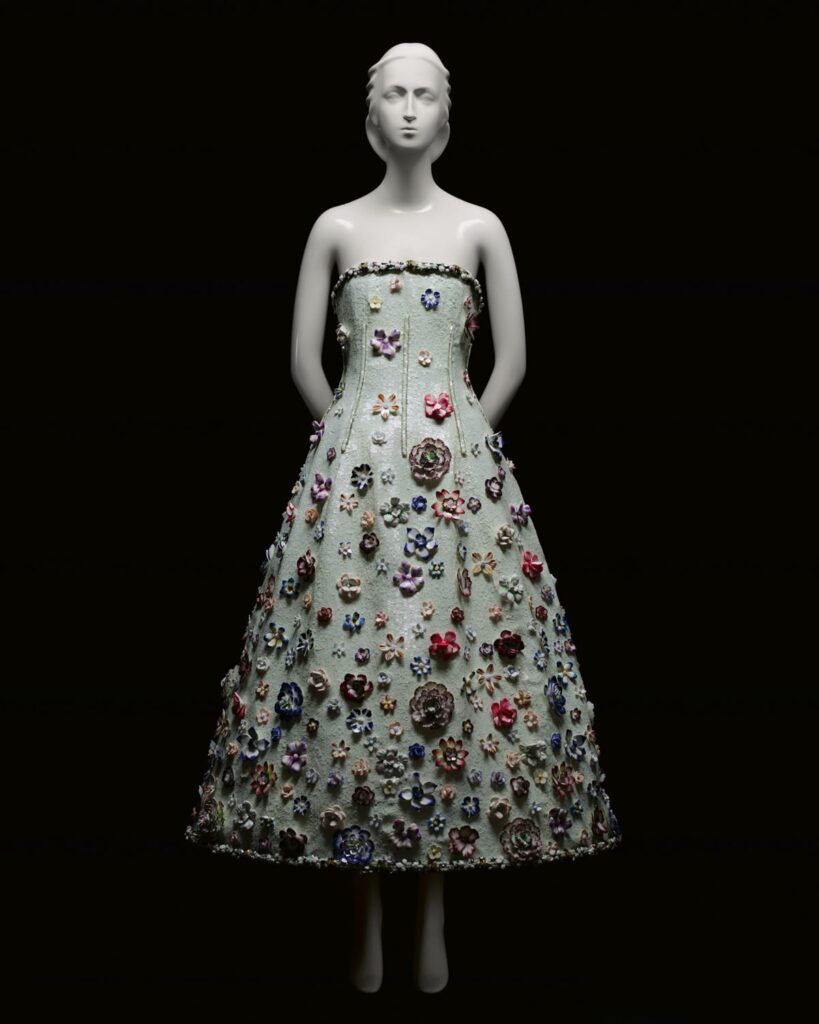

Bieff – who turns 80 on Jan. 23 – has kept clients coming back with his sculptural use of fabric and painterly approach to color. He begins with fine, textured fabrics, softly draped or cut on a bias to flatter as they accent a woman’s body – beaded chiffon, pebbly wool crepe with smooth satin, a hand-stitched ruffle here, hand embroidery or a band of sequin colors there.

But what is truly remarkable is the way he uses colors as washes – layered to give the design an opalescent quality; contrasted to heighten tension (much as Vincent van Gogh would juxtapose red and green, what he called “the colors of passion,” or blue and yellow); or gradated so that one color subtly blends into another for an ombré effect.

A native New Yorker based in Ossining, Neil honed his skill with and love of color at Syracuse University, where he studied painting, and abroad in Florence and Paris. (His love of sequins and knowledge of hand embroidery are the results of time spent in India.) He started his fashion career as assistant to couturier Arnold Scaasi, then went on to design suits and coats for Dan Millstein. Neil’s own label was born at his Genesis store on Madison Avenue in Manhattan, where yielding matte jerseys would be a bellwether for the shapely chiffons, velvets and wools of his later creations.

A career highlight was also a personal one – designing a bridal gown and dresses for the wedding of son Gwyn to Ikbal Bozkaya in Istanbul in April 2019. For this, he created a sleeveless V-necked bridal gown that was “a very shapely, very diaphanous mélange of different beads, sequins and alabaster stones on white silk chiffon over white silk charmeuse,” he told WAG magazine.

For the after-party, Neil made the bride a short silver halter dress with a sheer back, antique silver sequins, charcoal silk and trapunto stitching (a kind of quilting technique). “It was very young, very sexy,” he said.

Another Neil design saw Ikbal in a cap-sleeved black print dress, trimmed with black satin, whose V neckline and U-shaped back echoed her bridal dress.

No appreciation of Neil would be complete without talking about his deep relationship with Mary Jane Denzer – the store and the woman who founded it. He has called MJD “one of the best stores in the country.”

As for its meticulous founder, Neil recalled his first encounter did not go well as she proclaimed his choice of style and color for one client “a disaster.” But Neil persevered.

“After that, we often collaborated together. Mary Jane did have impeccable taste and an unerring eye. I would like to think we learned from each other, and it always ended up benefiting the client.”

Mary Jane, alas, is no longer with us, having passed in 2015. But her name lives on in the eponymous store, and Neil is set to celebrate the big 80.

So Happy Birthday, Neil – MJD’s “in-house designer” and dear friend.

Tags: Neil Bieff, Mary Jane Denzer, Debra O’Shea, Anastasia Cucinella, Dan Millstein, Istanbul, Florence, Paris, New York, Madison Avenue, Manhattan, Genesis, Syracuse University