“Karl Lagerfeld: A Line of Beauty” – at The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute in Manhattan through July 16 – celebrates the designer who transformed the houses of Fendi and Chanel and, with them, himself and the idea of the designer-impressario.

The German-born Lagerfeld (1933-2019) was an exacting, somewhat controversial figure known for his rigorous work ethic.

“Please don’t say I work hard,” he famously – and amusingly – once told Susannah Frankel of The Independent. “Nobody is forced to do this job, and if they don’t like it they should do another one. People buy dresses to be happy, not to hear about somebody who suffered over a piece of taffeta.”

The Met perhaps wisely eschews psychobiography for an exhibit that plumbs Lagerfeld’s gifts as a bewitching linesman – he saw sketching not as a means to a fashion end but an end in itself – and the connection among drawing, designing and presenting his creations in shows that became theatrical extravaganzas.

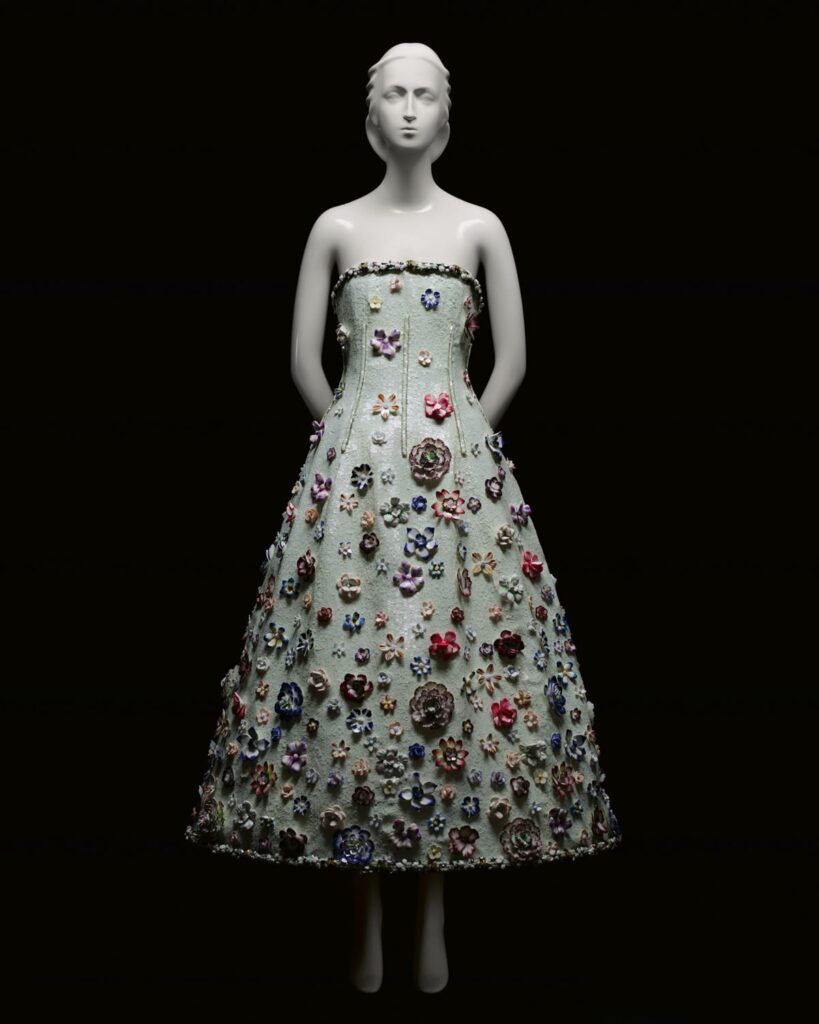

A fabulous example of this is a spring-summer 2019 haute couture strapless, appliqué cocktail dress from the House of Chanel that looks like a garden come to life. In the show we see the sketch, the dress and an image of the dress on a runway model.

That dress encapsulates Lagerfeld and the exhibit’s dual aesthetic, in which the straight line of the fitted bodice gives way to the serpentine line of the bell-shaped skirt. The straight line represents the Lagerfeld who was a classicist and modernist, the man known for angular black and white outfits that were not only a hallmark of Chanel but of his own personal appearance, which would become as iconic as any bouclé Chanel suit.

But there was also Lagerfeld, the romantic, as the garden-infused cocktail dress illustrates, the art history buff whose goddess gowns evoked ancient Greek and Rome; patterned dresses, the works of the medieval period and Renaissance; and pink, rose-appliqué creations, the Rococo of the 18th century. (In this, he was creating “a better future with enlarged elements of the past,” a phrase from the poet Johann Wolfgang von Goethe that he liked to quote.) The exhibit captures this duality with complements of its own – high and low pedestals in black-and-white galleries of angular and curving spaces.

The son of a businessman and a mother who encouraged their son to get about the business of being brilliant, Lagerfeld took himself off to Paris as a teenager, honing the drawing skills that were as natural as breathing in fashion illustration classes taught by Andrée Norero Petitjean at her school, Cours Norero.

While studying there, Lagerfeld submitted sketches with fabric swatches to the 1954 International Woolmark Prize, a fashion illustration competition organized by the International Wool Secretariat in which he took first place in the coat category. (Yves Saint Laurent won the dress division while Colette Bracchi triumphed in the suit section.)

This led to Pierre Balmain offering him his first official full-time position in 1955 as design assistant for Balmain’s “Florilège” boutique line. It was at Balmain and at the house of Jean Patou, where he became artistic director three years later, that he refined his style of sketching, which married technical drawing to the more playful fashion illustration.

But it was at Fendi, where he became creative director in 1965, and Chanel, where he became creative director in 1983, that his gift for transformation blossomed. At Fendi, he anticipated the trend to faux fur by using reclaimed pieces as fabric. As he once said, “You cannot fake chic, but you can be chic and fake fur.”

At Chanel, Lagerfeld reinvented the classic stateliness of the legendary but at that time moribund house, founded by Gabrielle “Coco” Chanel in 1910 – turning the interlocking Cs into a logo; revamping ready to wear, accenting accessories and giving the signature tweed suit a brighter palette and shorter hemline that has extended its life to everyone from Catherine, Princess of Wales to singer Olivia Rodrigo.

Along the way, Lagerfeld created an eponymous brand (in 1984) and transformed himself – dropping 90 pounds; writing a book about it, “The Karl Lagerfeld Diet” (2002); dressing in white Hilditch & Key shirts, offset by black – suits, fingerless gloves and glasses; and creating a private haven for himself and Choupette, his beloved Birman and an Instagram star with her own maids and diamonds, in a Paris apartment said to have contained 300,000 books.

Indeed, as The Met Store demonstrates, so iconic are Lagerfeld and Choupette that they are known through a line of T-shirts and accessories that have nothing to do with his couture.

Proving that among Lagerfeld’s greatest creations was himself.

Tags: Karl Lagerfeld, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Fendi, Chanel, Pierre Balmain, Yves Saint Laurent, Catherine, Princess of Wales, Olivia Rodrigo, Choupette, Jean Patou