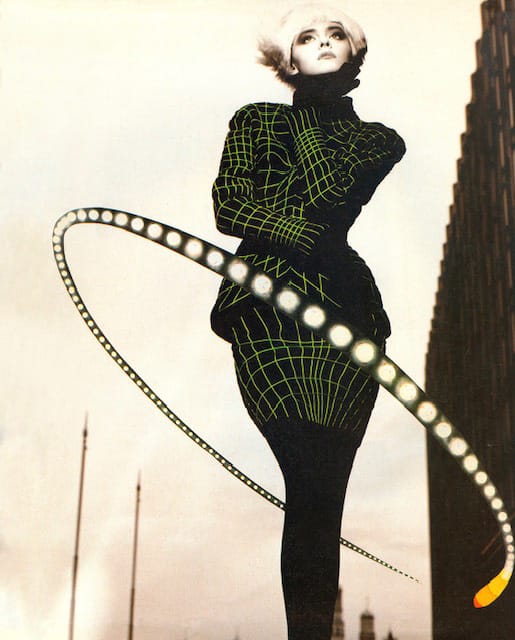

From the stage to the screen, the runway to the red carpet, there has always been an element of the theatrical in fashion. But French designer Thierry Mugler (Dec. 21, 1948-Jan. 23,2022) really imagined fashion as theater. His cutout creations, incorporating such unusual materials as plastic, metal, horse hair and feathers, offered viewers an erotic, sci-fi otherworldliness. At the same time, his broad-shouldered, cinch-waist “everyday” looks – drawing on the 1940s some 30 years later – ushered in the “glamazon,” the woman whose feminine silhouette presented sex as power.

Like actors who despise lifetime achievement awards, Mugler, who died of natural causes at his home in Paris at age 73, was not one for retrospectives. But you have to imagine he approved of “Thierry Mugler: Courturissime” (through May 7 at the Brooklyn Museum), a touring exhibit organized by the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts that has been seen by more than a million people since its launch in 2019. With more than 100 outfits, most of which have not been viewed before, the show encompasses videos, photographs, sketches and – a treat for noses – a heady special gallery dedicated to such Mugler fragrances as Angel (think praline crossed with patchouli), which was launched in 1992, introducing a new category of perfume, gourmand, even as it spawned many iterations over the late-20th and early-21st centuries.

“Courturissime” captures the Mugler idea of fashion as gesamtkunstwerk – a total work of art. And it does so in a thematic rather than chronological manner, exploring passions that ranged from the natural world to the erotic, fantasy, glamour and science fiction – although the show also has a timeline, because a little bit of history helps. Born in Strasbourg, France, Manfred Thierry Mugler’s childhood was defined not by fabric and scissors but ballet slippers. Dance would instill in him a love of costume and set design: In addition to a stint in the corps de ballet of the Opèra national du Rhin, he also studied interior design at the Strasbourg School of Decorative Arts.

Soon, however, he was creating clothes in London and then Paris, opening his first boutique in 1978. It was a moment when the more flowing, androgynous styles of that decade where giving way to the high glam, structured but also punk looks of the 1980s, the “Dynasty” decade, which dovetailed with Mugler’s sensibility. Having created a cinematic tour de force with its 2021 Dior show, the Brooklyn Museum goes all in with a designer who was far more theatrical – offering, for example, a life-size, 3-D hologram made by Quebec artist Michel Lemieux (Lemieux Pilon 4D Art) that embodies Mugler’s designs for a production of “La Tragédie de Macbeth,” presented by the Comédie-Française at the 1985 Festival d’Avignon.

“The actors were all in magnificent armor and breastplates, doublets, that were musculature, leather and metal,” Mugler said at the time, “while underneath they were vulnerable.”

This idea of armoring and stripping away plays out in sections on his collaboration with photographer Helmut Newton and the designer’s own Latexed fembots with their peekaboo bosoms and “derrièrre décolleté.” Installations of power suits (shoulder pads and peblum) and what appear to be mermaids or butterflies in bustiers also reveal and conceal.

Mugler would himself photograph and clothe some of the most famous female models and performers of his day, everyone from Cyd Charisse to Lady Gaga. But he didn’t neglect the masculine – designing for Michael Jackson and David Bowie and directing George Michael’s 1991 music video “Too Funky” – or anything in between or neither. (Mugler had a fluid sense of gender, sexuality and race long before such fluidity became a cause cèlébre.)

As “Too Funky” intimated, fashion was not enough. In 1997, the Clarins Group acquired a controlling interest in the House of Thierry Mugler. He left the house in 2002 to write, produce, direct and design.

“My only true vocation is the stage,” said the man who used actors as models, turned collection launches into arena extravaganzas and designed for Cirque du Soleil. As the exhibit demonstrates, that theatricality was not lost on the highest echelons of power. When he died, French President Emmanuel Macron observed, “Mugler had revolutionized French fashion and elegance at the end of the 20th century. His fashion shows were more than a show. They were grand performances, mixing fashion with theater and dance. We will miss his look and his audacity.”

For more, visit https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/exhibitions/thierry_mugler.

Tags: Thierry Mugler, Clarins, Brooklyn Museum, “Thierry Mugler: Courturissime,” David Bowie, Michael Jackson, Jerry Hall, George Michael, Cyd Charisse, Lady Gaga