When we think of great designers of couture for women, do we at first think of women designers?

Yes, we can rattle off names – Sarah Burton, who recently left the House of Alexander McQueen, Gabrielle “Coco” Chanel; Carolina Herrera; Jeanne Lanvin, Monique Lluillier, Donna Karan, Jenny Packham, Miuccia Prada, Elsa Schiaperelli, Vera Wang, Vivienne Westwood, to name a few. But don’t even more men designers come to mind? It doesn’t help that Burton was replaced by a man, Sean McGirr, creating an all-male leadership at Kering – the French luxury conglomerate, number two in the fashion world, that owns Alexander McQueen. It’s equally noteworthy that men were recently named to the top jobs at Moschino, Rochas and Tod’s.

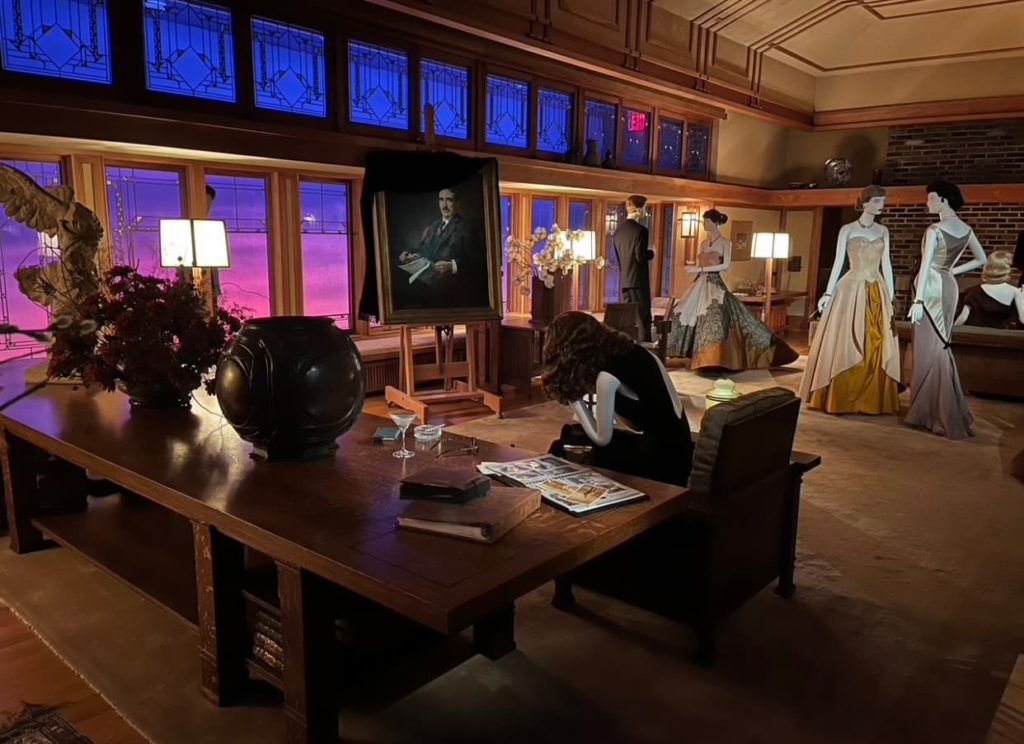

And yet there are not only great women designers but scores who are unsung. No longer: Through March 3, The Costume Institute of The Metropolitan Museum of Art presents “Women Dressing Women,” featuring 80 pieces from its collection by more than 70 makers. They include a black cocktail dress with spaghetti straps and a plunging neckline by Jasmin Sae of Customiety, who designs for women with achondroplasia, a condition that inhibits bone growth. (Diversity and inclusion is also served by plus-size mannequins and one in a wheelchair.)

In considering these works – selected by Mellissa Huber, the Costume Institute’s associate curator, and guest curator Karen Van Godtsenhoven for a show that was supposed to coincide with the centennial of U.S. women’s suffrage in the Covid year of 2020 – two words immediately come to our mind, “goddess” and “bold.”

The goddess begins really where the exhibit ends, “highlighting stories of absence or omission through the presentation of objects by designers whose work has only recently begun to receive widespread credit and recognition,” according to the press materials. These include the stories of Ann Lowe, the first African American to become a designer of note, who created Jacqueline Lee Bouvier’s ivory silk taffeta wedding dress for her marriage to then-Sen. John F. Kennedy on Sept. 12 1953; and Adèle Henriette Elizabeth Nigrin Fortuny, who was instrumental in the design of the silk, pleated “Delphos” gown, first introduced in 1909 after the chiton sported by “The Charioteer of Delphi,” an ancient Greek sculpture. (The chiton was worn by men and women alike.)

The 20th-century’s dawn saw a fascination with the fluidity of ancient Greek design. (Think dancer-choreographer Isadora Duncan.) But that flowing goddess look is echoed not only in a 1932 belted, cap-sleeved Fortuny incarnation but in gowns by Marcelle Chaumont, Claire McCardell, Marcelle Chapsal, Mad Carpentier and NoSesso.

Ensemble, Maria Grazia Chiuri (Italian, born 1964) and Grace Wales Bonner (British, born 1992) for House of Dior (French, founded 1947), cruise 2020, edition 2022. Gift of Christian Dior Couture, 2023. Photograph by Anna-Marie Kellen. © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

These watery designs are the yin to the bold, angular creations that vie for your attention as well. The robe de style by Jeanne Lanvin, a sleeveless cocktail dress with a shimmering, ballet-slipper pattern cascading down the plunging neckline, belt and front of the skirt. A red and plaid dolman-sleeved, fringed coat by Bonnie Cashin. A long red T-shirt by Katharine Hammett that exhorts you to “Stay Alive in 1985.” A fitted black jacket and bell-shaped skirt in bands of floral, red, brown and black patterns by Maria Grazia Chiuri and Grace Wales Bonner for Dior’s cruise-wear that echoes the “New Look” Christian Dior created at the end of World War II to celebrate the female silhouette and the return to romance. Jamie Okuma’s architectural, Art Deco-style “Parfleche Dress,” a black and tan fantasy. And Marine Serra’s fitted, scaly patchwork gown with extra-long sleeves.

All of these proclaim designers who have made a statement in creating for women who are unafraid to do the same.

Take note of their names. The Met has curated a show to make sure you don’t forget them.

Tags: “Women Dressing Women,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Costume Institute, Jacqueline Lee Bouvier, Ann Lowe, John F. Kennedy, Sarah Burton, Alexander McQueen, Gabrielle “Coco” Chanel; Carolina Herrera; Monique Lluillier, Donna Karan, Jenny Peckham, Miuccia Prada, Vera Wang, Vivienne Westwood, Delphos gown, Marine Serra, Jamie Okuma, the “New Look,” Christian Dior, Maria Grazia Chiuri, Grace Wales Bonner, Jeanne Lanvin, Bonnie Cashin, Marcelle Chaumont, Claire McCardell, Marcelle Chapsal, Mad Carpentier, NoSesso, “The Charioteer of Delphi,” Adèle Henriette Elizabeth Nigrin Fortuny, Elsa Schiaparelli, Kering, Mellisa Huber, Karen Van Godtsenhoven, Sean McGirr, Rochas, Tod’s, Moschino