The second part of The Met Costume Institute’s two-part exhibit on American fashion history is more American fashion than it is history.

The good news is that “In America: An Anthology of Fashion” (through Sept. 5) is better than part one, “In America: A Lexicon of Fashion.” The bad news is that its staging often sabotages its flights of inspired fancy. Forget designers and directors. The show could’ve used a choreographer and a traffic cop.

“Lexicon” gave us vitrines of clothing with words that matched the ensembles – or not – crammed into The Costume Institute in The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s lower level next to the Egyptian Wing. “Anthology” opens things up a bit, staging vignettes by edgy movie directors featuring mannequins clothed in various styles in The Met’s American Wing period rooms. The Costume Institute has done this brilliantly in the past with French fashion in European period rooms and a Vatican-inspired show that took us from The Met’s medieval galleries in the main museum on Fifth Avenue in Manhattan to The Cloisters, its medieval wing in Fort Tryon Park in northern Manhattan.

The problem with the current exhibit is that the rooms are generally too small to accommodate the fashion faithful thronging the show. (We saw it at a members’ preview that was already uncomfortable, given the museum’s masking and social distancing requirements.) The low lighting necessary for the preservation of the textiles in these rooms also makes it difficult to read the accompanying text. Unless you are intimately acquainted with film and fashion history, you’re going to give up in frustration.

Which is a shame, because “Anthology” has much to offer if you have the time and patience. Chinese filmmaker Chloé Zhao sets Claire McCardell sportswear in the light-dappled Shaker Retiring Room (Mount Lebanon, New York, 1835) in a scene that will evoke everything from Martha Graham’s “Appalachian Spring” to Margaret Atwood’s “A Handmaid’s Tale.” An operatic, Empire-style cocktail party turns chaotic as photographer-director Autumn de Wilde meets Jane Austen. Sofia Coppola goes all Henry James’ “Turn of the Screw” with Gilded Age-clad mannequins in the shadowy McKim Mead and White Stair Hall (Buffalo, New York, 1882-84). (Just forget about reading any of the text here. It’s not going to happen.)

In the show’s centerpiece, Tom Ford, designer and director, reimagines the battle between American ready-to-wear designers and French couturiers that took place in Versailles in 1973 as a “Matrix”-flying encounter, with swords brandished and clothing swirling in the Vanderlyn Panorama Room, a stately 360-degree view of Louis XIV’s pleasure palace. It’s a tour de force but again unless you have a deep knowledge of fashion, it’s going to be hard to match the text beneath the panorama with the soaring, El Greco-like apotheosis of outfits.

Nor do the show’s organizers necessarily help themselves with the mix of periods. A room of businesslike 1940s fashions is inextricably linked with music of the freewheeling 1920s. A fabulous strapless, floral-brocade cocktail dress placed in the Rococo Revival Parlor (Astoria, Queens, circa 1850) so confused one viewer that his wife had to explain five times that though the dress was from the 1960s, the room was mid-19th century. (He still didn’t get it.)

Along the way, the exhibit considers the unsung role that Black designers, tailors and seamstresses played in American fashion. There’s the well-known striped dress that first lady Mary Todd Lincoln wore with a Tiffany seed-pearl suite her indulgent husband, President Abraham Lincoln, gave her. The dress was presumably created by former slave Elizabeth Keckly, who stood in relationship to the first lady much as Angela Kelly stands in relationship to Queen Elizabeth II today – dressmaker turned confidante. (Though Mary Todd Lincoln appears stout in photographs, particularly standing next to her gangly husband, the exquisite, wasp-waisted day dress looks like it could be worn only by a child today.)

You wonder if the extraordinary Keckly, who would go on to become a civil rights activist, inspired Ann Lowe, the Black designer who created Jacqueline Lee Bouvier’s ivory, portrait- neckline gown for her Sept. 12, 1953 marriage to then-Sen. John F. Kennedy. (That moment is recalled in a photograph in a room about famous bridal gowns.)

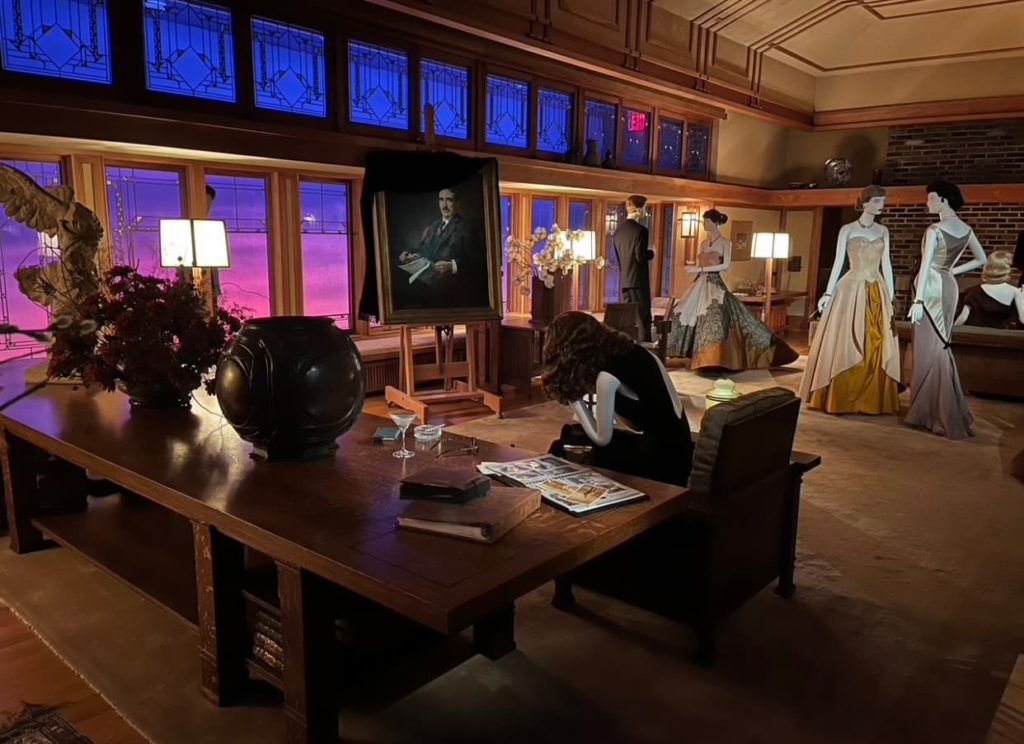

The patient will be rewarded with such golden nuggets. The impatient will find themselves straining to see Martin Scorsese’s Hitchcockian homage in the Frank Lloyd Wright Room (Wayzata. Minnesota, 1912-14), complete with 1950s gowns, and recognize a familiar New York experience – eager to be part of a scene if f only they could get into it.

Tags: The Costume Institute, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, “In America: An Anthology of Fashion,” Chloé Zhao, Claire McCardell, Tom Ford, Versailles, The American Wing, Elizabeth Keckly, Mary Todd Lincoln, Jacqueline Lee Bouvier, Ann Lowe, Martin Scorsese, Frank Lloyd Wright, Henry James, Jane Austen, John F. Kennedy, Abraham Lincoln, Black designers, McKim Mead and White, Sofia Coppola, Alfred Hitchcock